Why does Cricket have a problem valuing young players?

Would a transfer market solve the issue?

What do Mason Crane, Feroze Khushi, Scott Currie, Lewis Goldsworthy and Shoaib Bashir have in common?

In addition, these five players have almost the same thing that they have in common with Harry Duke, Ben Green, Ben Allison, Conor McKerr and Amar Virdi.

What is it?

Crane, Khushi, Currie, Goldsworthy and Bashir are promising young players who have had to get a loan move to another county in order to play the T20 Blast. The other five join them in either being high potential players or previously high potential players having to obtain a loan move to another county in order to play in the County Championship.

Of these players, three play for Somerset, two for Hampshire, two for Surrey and two for Essex. Four of the stronger Division One teams and generally decent T20 sides as well (they were the four qualifying teams from the South Group last year, and three of the four teams are in qualifying spots this season). So, there’s a common denominator there as well.

Essentially, these players are, to use a regularly used term, ‘blocked’ at their current county. To explain that term further, their first-team prospects at their county are generally limited due to higher-profile players in their playing role.

A thriving loan market is a good thing for these players. They get game time and their parent club gets to assess them. A ‘smaller’ county taking them gets the benefit of a talented young player, although there’s a decent argument to make that in the long-term the smaller county is losing out, given the fact that they are developing a player for a rival ‘bigger' club, for free. The main issue for these young players is that some counties are completely unaware of which of them represents high potential talent - the scouting network in county cricket isn’t particularly good.

The most astute way that a smaller county can take these young players on loan is when they take the player on loan with a view to a permanent move - e.g. the young player is going out of contract that season. In my roles in county cricket, I update an out of contract database in order to keep an eye on these opportunities.

When I was at Leicestershire, this is how Rishi Patel was recruited (from Essex), and to an extent, Tom Scriven as well from Hampshire (he was trial rather than loan, but it’s broadly the same thing). Both signings have worked out extremely well subsequently.

This way, the smaller club can sell themselves to the player, and make it clear that they are offering far greater playing opportunities than their parent club. Such a strategy would work especially well once there becomes evidence of this structure working well, where teams can illustrate that players taking a similar route have developed their career quickly.

There’s a very good argument to suggest that a number of talented young players sign one too many contracts at ‘bigger’ counties and if they’re not breaking through to the first team by 21/22 then they should look at other opportunities. If I was Director of Cricket or Head of Recruitment at a smaller county, I would be permanently on the lookout for these players.

If, at that stage, the player signs a new contract at their bigger county, then you have your answer - they either have an unrealistic expectation of their game time, or they don’t want to move from the bright lights of London (e.g. Surrey/Essex players). Either way, they don’t fit your recruitment model.

When I was scouting the T20 Blast ahead of the Wildcard Draft for The Hundred, I was struck by how little game time was given to young players. Red-ball nurdlers were picked ahead of younger, high intent & higher upside players. I was expecting more from counties in terms of picking young talent.

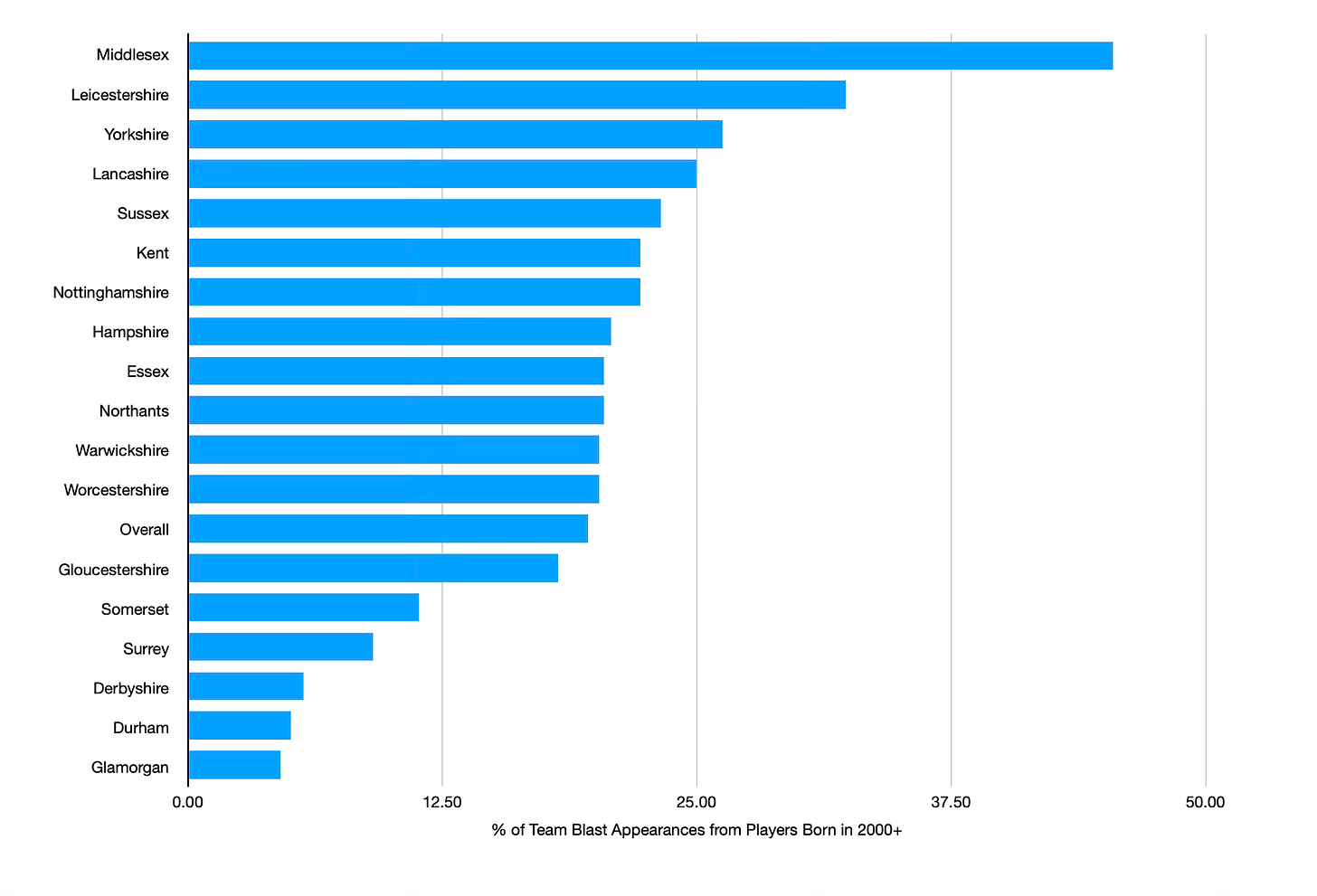

Given this, I collated T20 appearance data from the 18 counties in the Blast so far (up to and including matches played on Friday, 5th July) to see which counties gave young players the most opportunity.

First of all, a look at percentage of Blast game time given to players born in 2000 or later (aged 24 or below this year):-

Age 24 shouldn’t really be considered young for players. Yes, it’s definitely before peak age, but it’s hardly illustrative of a player who is finding their way in a sport. Certainly, football is rather different - more on that later.

This year in the Blast, no county has given 50% or more game time to players born in 2000 or later. Four counties (at the bottom of the chart) have given less than 10% of their game time to players in this age range, with the overall average being just below 20%.

I was aware that young players weren’t getting as much opportunity as they should in county cricket, but these figures illustrate that to a greater degree than I even imagined. Certainly, it would be interesting to ask questions of the decisions taken over a long period of time at several counties in particular, given their low percentage of game time given to players this year in The Blast, mediocre results in recent years and historical lack of contribution of players to the England team as well.

If you think these numbers overall are bad, then prepare for things to get a whole lot worse. Here’s the percentage of Blast game time given to players born in 2002 or later (aged 22 or below this year):-

On average, a mere 6.94% of game time from Blast teams was given to players born in 2002 or later. Nine teams - half of the Blast - gave 2002+ born players less than 5% of their game time, with three teams giving zero games to players in this age bracket.

Credit goes to Middlesex and my former county, Leicestershire. Both counties have had well-documented financial challenges in recent years, but feature at the top of both charts, illustrating that they are now looking at sustainable progress via younger, more cost-effective playing staff.

If you are reading this and are a young player at a county, or their agent, this should put the opportunities into sharp perspective. Just 27 players born in 2002 or later have featured in the Blast this year, and many of those have played once or several times.

As a national team, England and the ECB should be extremely concerned about these findings. A number of county teams are evidently not giving much game time to young talent, and potentially are focusing on short-term results and job preservation of coaches as opposed to offering a strong pathway to international and franchise cricket.

This has to change, but I have little confidence that it will, particularly in the short-term. An innovative solution could be to have an ‘Under 23 XI’ competing in The Blast, similar to how the old Unicorns was structured, featuring young talent which are still in contract with a county but have previously not been given many opportunities previously.

Look at this 25 man squad which could be created from that talent pool this season (players born in 2000 or later who have played two or fewer T20 Blast matches in 2024):-

Ben McKinney, Charlie Allison, Will Smale, Jack Morley, Roman Walker, Alex Russell, Sonny Baker, Tom Lammonby, Tom Clark, Shoaib Bashir, Harry Duke, George Thomas, Ben Geddes, Theo Wylie, Robin Das, James Rew, Will Luxton, Harry Moore, Yash Vagadia, Yousef Majid, Harsh Parmar, Harris Ajaz, Jamal Richards, Kasey Aldridge, Dom Kelly.

In an 18-county structure, many of these should be getting a great deal more game time than they currently are getting. With a decent coaching and analytics staff, I’m pretty sure this group would compete, at the very least. I don’t think it would come bottom of the (stronger) South Group, and I think it could fare slightly better in the North Group.

Not only that, but it would give great levels of game time against decent opposition, leading to more Blast game time at their parent county and then chances in both the Hundred and other franchise leagues - and possibly accelerating the process towards England selection too.

So, if anyone at the ECB is reading this and wants to fund such an enterprise, please feel free to get in touch at sportsanalyticsadvantage@gmail.com.

Moving on, a quick discussion on this from an IPL perspective. Anyone interested in a look at how young players represent far better value than older players in the IPL can view my post here.

Ahead of a three-year auction cycle, this is the time for IPL teams to invest in young players - they can get good prospects with three-year retention rights, potentially for as little as 1 Crore or less at auction.

The problem is that without a football-style transfer market, IPL franchises don’t have much of an incentive to develop their own players. The IPL auction structure means that, because of limited retentions in mega auctions, a team will be unable to retain talent they develop from their own academy. So, other teams would benefit from the time and money spent on developing academy players.

Counties might feel a similar way. If a player is developed in their academy and plays for England, they rarely get use of that player. A development fee is given, but it is debatable whether this is in line with the loss for the county. If a county develops a player and that player plays in the IPL or other franchise leagues, it doesn’t get a loan fee - and there’s a decent argument to suggest that they potentially should.

In my view, changes to county structures need to be made to incentivise giving more game time to younger players. A football-style transfer market would be one way. Another way would be to make it financially beneficial for counties to pick Under 23 players, in a similar way to already exists with them picking players who are immediately qualified for the national team.

Football (financially, a more mature industry than cricket) already has these kind of incentives in place. A team can develop young players and financially benefit by selling them, and receiving sell-on clauses as well - it makes the entire process worthwhile.

Watching the France versus Portugal match in the Euros last night, I was impressed with the composure of Bradley Barcola converting a penalty in a knock-out shootout in the quarter-finals of a major tournament.

Barcola, born in September 2002, already has achieved plenty in his football career. International football, plus 65 matches in the top flight in France, nine goals, sixteen assists in those matches, and a 45m Euro move from Lyon to PSG last summer.

According to flashscore.co.uk, Barcola has a market value of 40.8m Euros at the time of writing. Transfermarkt is a little higher, at 50.0m. Whatever value is accurate, it is clear that Barcola is a financial asset to both PSG and his former club, Lyon.

21 year olds playing this volume of matches rarely exist in cricket. There are a few, but they’re few and far between. In football, because there are huge incentives to give young players game time, they are much more prevalent.

Let’s have a look at the players born in 2002+ in the squads of the eight quarter-finalists in Euro 24. The figure in brackets is their valuation at the time of writing via Transfermarkt (in Euros):

Spain: Fermin Lopez (30m), Nico Williams (60m), Lamine Yamal (90m)

Germany: Jamal Musiala (120m), Florian Wirtz (130m), Maximilian Beier (30m)

France: Eduardo Camavinga (100m), Warren Zaire-Emery (60m), Bradley Barcola (50m)

Portugal: Nuno Mendes (55m), Antonio Silva (45m), Joao Neves (55m), Francisco Conceicao (22m)

Switzerland: Leonidas Stergiou (5m), Ardon Jashari (6m), Fabian Rieder (8m)

England: Jude Bellingham (180m), Adam Wharton (30m), Kobbie Mainoo (50m), Cole Palmer (80m)

Turkey: Ahmetcan Kaplan (10m), Arda Guler (30m), Kenan Yildiz (30m), Semih Kilicsoy (12m), Bertug Yildirim (3.5m)

Netherlands: Bart Verbruggen (18m), Ian Maatsen (40m), Xavi Simons (80m), Ryan Gravenberch (35m), Brian Brobbey (35m)

So, the squads of the eight best teams at Euro 24 have a total of 30 players born in 2002 or after, with every team having at least three in their squad. These 30 players have a market value far in excess of 1 billion Euros, based on these Transfermarkt valuations. In football, young talent is a valuable commodity, while in cricket (without a transfer market) this is often far from the case.

To conclude, let’s look at how many 2002+ born players featured for the major teams in the recent T20 World Cup:

India: None

Pakistan: Saim Ayub, Naseem Shah

Australia: None

England: None

Afghanistan: Mohammad Ishaq, Noor Ahmad, Nangaliya Kharote (they also had a number of 2000 & 2001 born players)

New Zealand: None

West Indies: None

Bangladesh: Rishad Hossain, Tanzim Hasan Sakib

South Africa: None

Sri Lanka: Matheesha Pathirana, Dunith Wellalage

To finish, a few rhetorical questions.

Which sport is right? Football, with 30 players born in 2002+ in the best eight teams in Euro 24, with a combined market value well in excess of 1 billion euros, or cricket, whose 10 main teams in the T20 World Cup chose nine players in the same age range between them?

Which sport is far more developed financially? Football.

Which sport has many teams run (as Sporting Directors or Directors of Football) by people with little or no playing history? Football.

Which sport has a management structure pretty much exclusively run by ex-players? Cricket.

I think that by this stage readers will know what my point is. The good thing for astute cricket teams is that there is so much growth, and ‘quick-wins’ possible with good planning and structure.

Anyone interested in discussing how I can help their team with strategic management and data-driven analysis, or contribute to any media work, can get in touch at sportsanalyticsadvantage@gmail.com.

At the end, the ex-cricketers should also understand that it is not bureaucracy. It is meritocracy and since people who are experienced in managing recruitment side or the management side should be of more importance, despite them knowing "little less" than the ex-cricketers