Morgan and Warner

What's causing their struggles?

Rewind back to Thursday - Kolkata Knight Riders versus Mumbai Indians. In what was an almost perfect display, KKR got the better of MI by seven wickets, restricting them to 155-6 and then chasing it with 29 balls to spare.

I say almost perfect, because the match featured another failure from captain Eoin Morgan. Coming in at number four with 28 runs needed, the KKR think-tank probably thought that this was the perfect time for Morgan to get some time in the middle, pick up a nice red inker and finish off an easy chase - but the England captain was dismissed again for less than a run a ball.

The similarly aged David Warner has also had his travails this year. The Australian was dropped - both from the team and the captaincy - in the last game before this year’s IPL was paused, before regaining his spot as opener as the tournament resumed in the UAE. Subsequent returns of 0(3) and 2(3) of course, are not positive.

Both players have something else in common - they are similarly aged. Morgan has just turned 35 years of age, while Warner will do so in around a month’s time. As the saying goes, all good things must come to an end, and if the reasons for the performance issues for both players are age-related, that’s certainly nothing out of the ordinary. However, in the case of Morgan in particular as we will discover, he had a renaissance in 2019 and 2020 after mediocre 2015-2017 seasons, so it may not be related to that. In any case, the purpose of this article isn’t to criticise or to write off players, it’s more to do with using data to show some underlying reasons why the performance levels of these players in recent times aren’t as good as they have been.

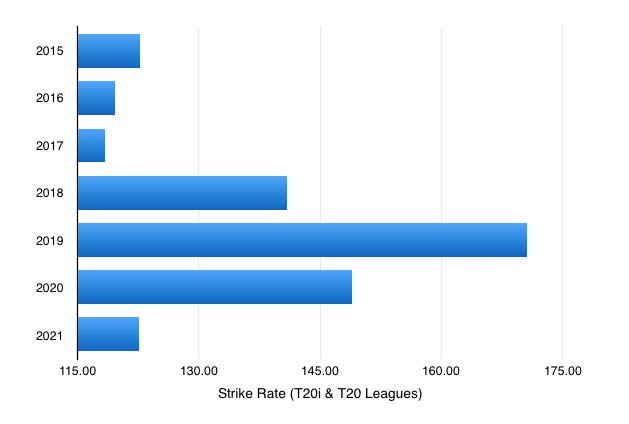

There was a time, around 2016-2017, when I was getting into cricket analytics, where I probably thought Morgan was the most over-rated cricketer in the world. This was something I struggled to understand, because people seemed to talk about him as if he was a legend, yet in the preceding couple of years, he had really struggled. Then, around 2018, it was like something flipped a switch inside him and he turned into being a much more attacking player, full of intent and boundaries, which naturally translated into higher strike rates, as shown below:-

There is little doubt that Morgan’s strike rate in 2019 was truly world-class. I don’t think I’d ever seen a turnaround from a player - considering their previous numbers. However, there’s been a marked drop off this year, where he’s gone roughly back to 2015-2017 levels. Based on the above, it would be pretty reasonable to say that you couldn’t blame KKR for purchasing Morgan for 5.25 Crore in the auction ahead of the 2020 IPL season, although it would also be pretty reasonable to say that they should be concerned about his 2021 level. So, of course, should England be, ahead of the T20 World Cup taking place in a month or so’s time.

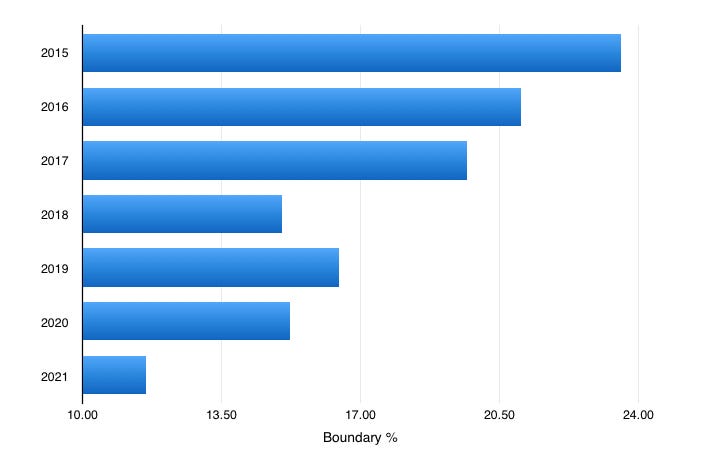

The reasons for Morgan’s struggles, then dominance, and then struggles, are pretty obvious when looking at some underlying data:-

Here we can see why Morgan struggled in 2015-2017. He had low boundary percentages in conjunction with a relatively high dot ball percentage - the ideal recipe for a low overall strike rate. In 2019 and 2020, his boundary percentage figure took a huge upturn and in 2019 it was elite level (particularly along with hitting sixes in almost 12% of balls faced). However, in 2021, his numbers are again around that least ideal top-left corner, similar to his 2015-2017 output. Morgan urgently needs to get his boundary-hitting mojo back in order to add value to his teams.

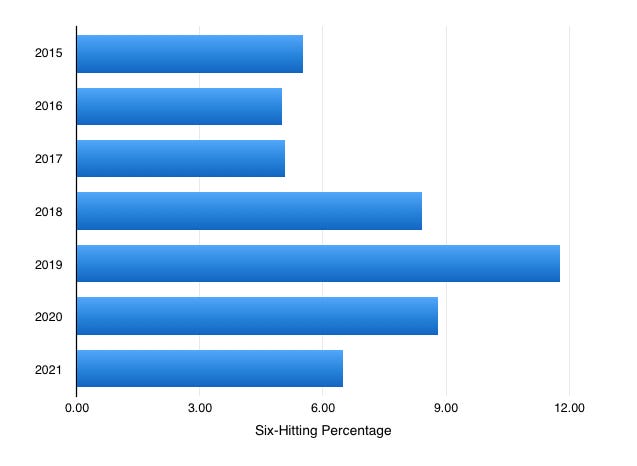

Morgan has always been a pretty decent six-hitter. Even in those lean years from 2015-2017, he hit at over 5% of balls faced, peaking at almost 12% in 2019 - an incredible figure:-

Again, though, Morgan’s 2021 has seen his six-hitting reigned in to around those 2015-2017 levels, just like his overall boundary and dot ball percentages. Above 6% is still very, very good, but compared to recent years, it’s not nearly as impressive.

The final problem Morgan is having this year is that he’s getting out more often than in recent years. Balls per dismissal and boundary percentages for players are fascinating ‘trade-off’ metrics because very few players can excel at both, because players generally either trade-off defence (stability) with attack (hitting) or vice versa. If you can get over 20 balls per dismissal and 20% boundaries in conjunction, that’s a pretty decent achievement for a frontline batter:-

This was where Morgan was at in his renaissance years, 2019 and 2020. However, he has been nowhere near that in the other five of his last seven years, and this year is particularly concerning, showing a low boundary percentage in conjunction with a low balls per dismissal. Essentially, he’s getting out frequently without being able to hit boundaries well either - and that’s a disaster for any batter.

You can see that there are clear, marked, differences between Morgan’s yearly performance output, and I hope, for England’s sake, that he can get back towards his 2019-2020 levels. The next couple of months look critical in shaping Morgan’s future career.

Taking a trip back to when I was getting into cricket analytics at around 2016-2017, I can remember how good David Warner was. Warner was a batter who struck fear into bowlers worldwide in T20 cricket, managing to achieve the previously mentioned feat of combining high balls per dismissal with high boundary percentages. Not only this, but Warner’s balls per dismissal were incredible - anchor batter territory - but without the negative trade-off with low boundary percentages. He was, put simply, an absolutely world-class T20 batter.

Then came 2018. You don’t need me to go into what happened in 2018 to Warner, but statistically, something also changed in him. He appeared to start taking a more responsible approach to his batting - his boundary percentage markedly dropped:-

None of the last four seasons have seen Warner hit over 17% boundaries, a figure which is broadly the benchmark for an average T20 batter. This year has seen a new low, with his boundary percentage just shy of 12%. Unfortunately, current boundary output is not a positive for his teams, and is a part-reason as to why Sunrisers Hyderabad have struggled this season.

We can see the impact that this has on his strike rate, too. As boundary percentage has dropped, so has his strike rate, and this is logical - as I’ve written about numerous times, there is a direct relationship between the two metrics. Dot ball percentage has also worsened in 2021:-

Those high boundary percentage seasons in 2015 and 2016 in particular, translated into high strike rates - unsurprisingly. However in 2018, Warner’s dot ball percentage markedly increased, and this - in conjunction with around a 5% drop in boundary percentage - caused his strike rate to plummet. It would be fascinating to know if someone told Warner this about his dot ball percentage around that time, as in 2019 and 2020 it visually seemed like he tried to become a ‘dot-ball avoider’. Data backs this subjective point of view up as well, with extremely low dot ball percentages in those two years, but the problem with this approach is that without a high boundary percentage, it is virtually impossible for a batter to strike over 140 (see his 2020 season).

2021 has been a real problem for Warner. As you can see above, his boundary percentage has dropped even further and, in something of a double-whammy, so his dot-ball percentage has also risen sharply. When these two things coincide, it’s no surprise that his strike rate has declined hugely. High dot ball percentages are tolerable, or indeed, acceptable, when players hit a high percentage of boundaries, but when a player hits far below average for boundary percentage and dot-ball percentage is this high, it’s a huge problem.

What Warner has been pretty consistent at is balls per dismissal. Only one season, in 2018, featured below 20 balls per dismissal so despite several recent failures in the IPL, he can’t be accused of throwing his wicket away in general. But facing 20+ balls and hitting at a low strike rate is not a positive for any player or the team they play for, and this must be addressed by Warner if he is to become an asset for a T20 team in the future. It will be fascinating to see if he can do so in the remaining few matches for the already-eliminated Sunrisers Hyderabad - if he continues to be selected by them - and it will also be fascinating to see if he has any takers in the IPL mega auction coming in the next few months. Peak Warner, as we saw from his 2015 and 2016 data in particular, would go for many, many Crore - at least 10 Crore would be likely - but a player hitting less than 12% boundaries and striking at sub-110 should, in an efficient market, see no demand.

It is sometimes difficult for teams to know when to move older players on, but every player at some latter stage of their career will have a decline in them which they cannot turn around - it’s why players retire. Fans too, often judge a player on what they did at their peak, as opposed to their current or expected future output. Smart recruiters see past the name and solely judge players on the level they are expected to produce in the future. Only time will tell whether the declines in Morgan and Warner this year are terminal, but hopefully this article does provide some insight into why their numbers have dropped this season and what they need to do, in terms of intent at least, to get back to previous peak levels.

Hi Dan - Very interesting analysis and I agree with your overall assessment. It looks like KKR is carrying Morgan the passenger and at some point McCullum will need to take his adage "If you cant change A man, change THE Man" and apply it to Morgan too.