It's not as simple as 'take more risks, score more runs'

South Africa at the World Test Championship

There are 168 posts on this Substack - congratulations if you have read all of them!

So if you're here, you’re probably someone who cares about what actually wins games of cricket - not just highlight reels, but the numbers and the business behind them.

Serious sports analysis shouldn’t be behind a paywall—but it still needs your support.

I regularly dive deep into the numbers behind the game - uncovering patterns, exposing myths, and offering insights you won’t hear on TV or see in mainstream coverage. This isn’t after timing or inane stats. It’s real, independent sports analytics - and it takes hours of research, analysis, and writing.

If you’ve found value in this work, now’s the time to step up.

Subscriber support is the only thing keeping this newsletter alive. I have no big media backing, and no advertisers. This Substack only has readers just like you who care about data-driven, smart cricket analysis.

👉 Become a paid subscriber or make a donation today - even a small contribution makes a huge difference. Every contribution, big or small, helps me dedicate more time to creating meaningful content

If you think the game deserves better analysis, help me to keep delivering it.

After day one of the World Test Championship Final at Lord’s, there’s been a lot of criticism of South Africa’s negative approach with the bat in reply to Australia’s 212 all out.

Certainly, 43-4 from 22 overs isn’t pretty, but both teams have struggled with the bat so far in this match - a predictable outcome given the bowling strength of both teams (particularly Australia) yet the question marks surrounding numerous batters and their roles on either side.

Kevin Pietersen on X was among those referring to South Africa’s approach:-

Others asked what can be achieved by blocking everything for 20 overs, with general suggestions that being something like 75-5 would be better, and that this anti-England approach should get criticized the same way as over-aggressive batting.

Unfortunately, this is a very first-level point of view - I’ve got a slightly different thought process, and I’ll explain it here.

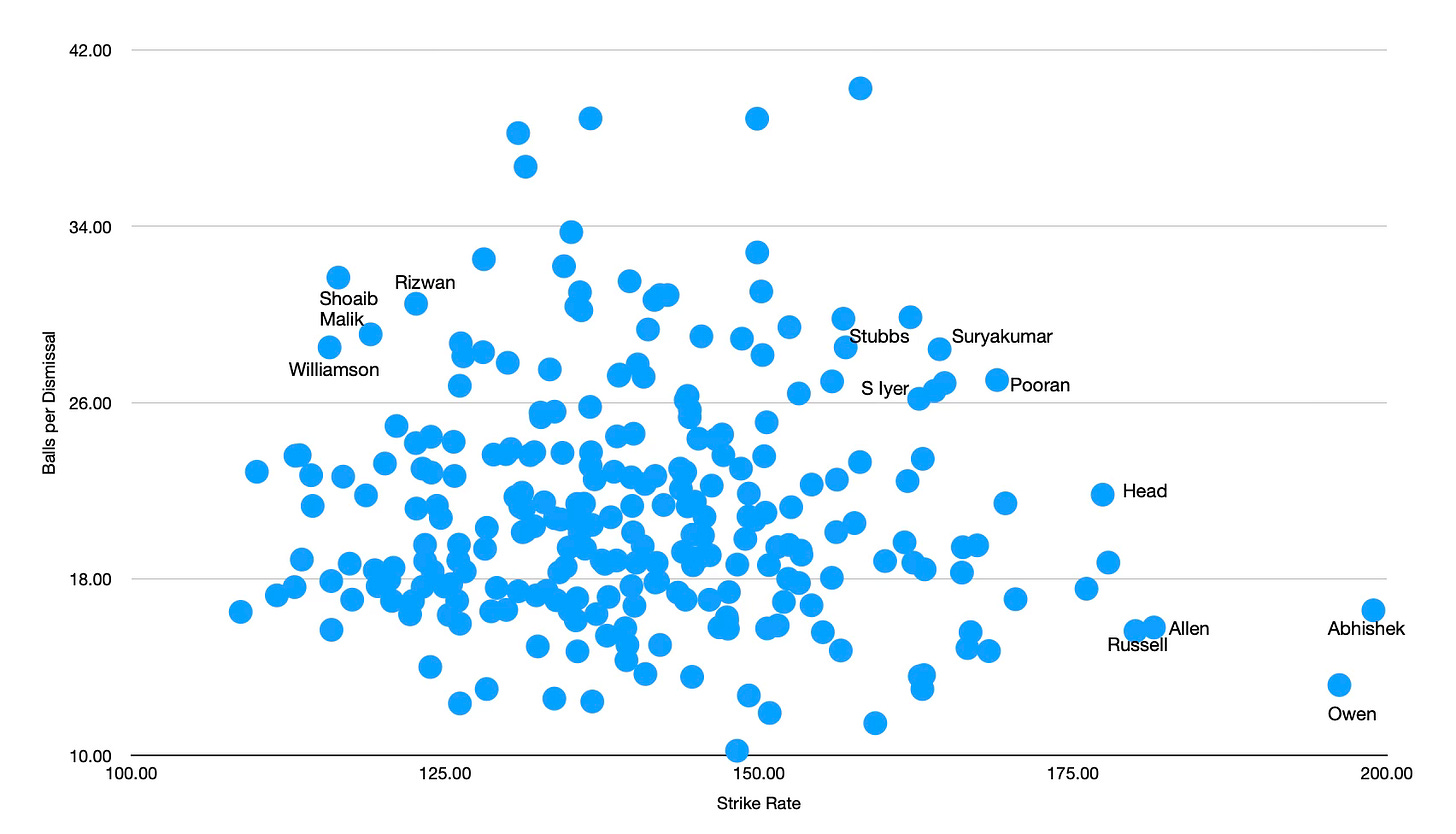

When we talk about a player’s strike rate and balls per dismissal as two example basic metrics, we can draw a number of conclusions as to the player’s general approach. Over a big sample, we can say that if a player’s strike rate is high, and balls per dismissal is low, then they have a high risk/high reward approach. Examples of this type of player in T20 might be Abhishek Sharma, Mitch Owen, Phil Salt, Sunil Narine and Finn Allen.

On the flip side, we can say that if a player’s strike rate is low, and balls per dismissal is high, then the player has a stability oriented approach which produces mediocre strike rates but they get dismissed less often than the average batter. Examples of this type of player in T20 might be Kane Williamson, Shoaib Malik, Cameron Bancroft and Mohammad Rizwan.

I’ve deliberately used either extreme here because these two metrics (strike rate and balls per dismissal) tend to have a reverse relationship. To spell it out, if a player’s strike rate and balls per dismissal figures are both high over a big sample size, they’re world class, because they score quickly and don’t get out as often as the average batter - examples currently would be Nicholas Pooran, Suryakumar Yadav, Shreyas Iyer, Tristan Stubbs and to a slightly lesser extent from a balls per dismissal perspective, Travis Head and Heinrich Klaasen.

Conversely, if a player’s strike rate and balls per dismissal figures are both low over a big sample size, they’re not very good. I’ll spare the blushes of the players who fit into this category in recent years.

Here’s a look at this in decent-level T20 since the start of 2024:-

You can see that no player is in the upper top-right corner, because it’s basically impossible to strike at 180+ and have 30+ balls per dismissal. A player would have to be able to execute at a level never seen before when playing ultra-aggressive shot options to achieve this.

The players in the bottom-left corner (low strike rate and low balls per dismissal) should, in an efficient player recruitment market, be either what I call ‘extra-depth all-rounders’ - e.g. frontline bowlers who can bat, but can’t hit - or batters who don’t get recruited by teams. The fact that some of the players in this bottom-left corner do get recruited, and sometimes for decent money and playing prominent roles, speaks volumes about the inefficiency of cricket recruitment and player trading.

Identical reasoning can be related to Test cricket, and the reason why is clear-cut. Strike rate and balls per dismissal (as well as numerous other metrics) are simply the outcomes of a batter’s shot options, and how good they are at executing them.

The reason why Abhishek, Owen, Salt, Narine and Allen have a high strike rate and low balls per dismissal is because they take a relatively high percentage of ultra-aggressive shot options which are more likely to result in both boundaries and dismissals - think about shots like pulls, slogs, slog-sweeps, reverse-sweeps and ramps.

On the other hand, Williamson, Shoaib Malik, Bancroft and Rizwan take a relatively high percentage of defensive or rotational shot options which are less likely to result in both boundaries and dismissals - think about shots like pushes, working into gaps, leaves, and forward/backward defensives.

In Test cricket, this might be equated to playing at balls which are bowled in good areas - for example, pacers hitting a good length with the line between 3rd and 5th stump. A player like Zak Crawley has been criticized a lot for playing too aggressively at these type of balls, but you can’t have it both ways - if you play at these balls too much, or too aggressively, then you have a higher risk of being dismissed.

However, a batter can also can get off to a flier and take the game away from the opposition if it works out for them - England, and Crawley’s viewpoint, presumably, is that the reward justifies the risk.

South Africa decided not to take that risk. Their approach was to generally take non-aggressive shot options with a higher balls per dismissal expectation, but lower scoring expectation, to see off the threat of the Australian pacers with the new ball. It’s not an unreasonable strategy, by any means.

After 22 overs on day one, and being 43-4, we can see that this approach wasn’t successful on this occasion. But that’s all it was, one occasion. It doesn’t mean that they are right or wrong. If they played this out 1,000 times, for example, a percentage of times they would have a similar score to 43-4, other times they might be 45-0 or 50-1, and other times they’d be 45-6, and a whole array of other scorelines.

Who is to say that if they went out and tried to play more positively, they wouldn’t be 70-7 at the close, and then perhaps the same people who criticized them will likely say that they were too reckless. And this is the entire problem with criticizing after the event - if you want your opinion to have gravitas, and real predictive value, you need to give that opinion BEFORE the outcome, not after it. That’s just being the master of hindsight, and we see it all the time on commentary and on social media.

South Africa had a clear plan and approach and it didn’t work out on the day - it doesn’t mean that they were wrong.

Anyone interested in discussing how I can help their organisation with strategic management, data-driven analysis and long-term planning can get in touch at sportsanalyticsadvantage@gmail.com.

100% agree with everything said here.