IPL Auctions - Market Dynamics Series Part 2 - Player Ages

Analysis illustrates a huge market inefficiency in valuing players

Part one of this series of writing about the market dynamics of the IPL auctions can be viewed here. This gives an introduction to some of the areas which will be discussed in the coming pieces of writing in the series.

I spoke a little about the stages of the auction cycles in part one and how that these can change the constantly changing market value of players both in the tournament and for the available talent in the auction pool, and I want to get into much more depth here on the topic of player ages, and how current expected performance levels are not the same as future expected performance levels.

I also will talk about the skewed market valuation of certain types of players and how that leads to major market inefficiencies in terms of player valuations - which is a dynamic which can ultimately be exploited by those franchises whose recruitment teams are smarter than the others.

The first place where I want to start is the age dynamic with a general focus towards batters and bowlers - one of the biggest market inefficiencies you will ever see. As I’ve written about many times before, constructing a strong bowling attack is a non-negotiable for teams to succeed.

While this may sound obvious, it’s worth noting that some teams have pretty much never achieved this in the history of the IPL, and have prioritized their budget resources on batters instead. Put simply, it’s only obvious if you know about it and have the willingness to act upon that knowledge - and there’s evidence to suggest that some teams either don’t know or don’t care about such a thing.

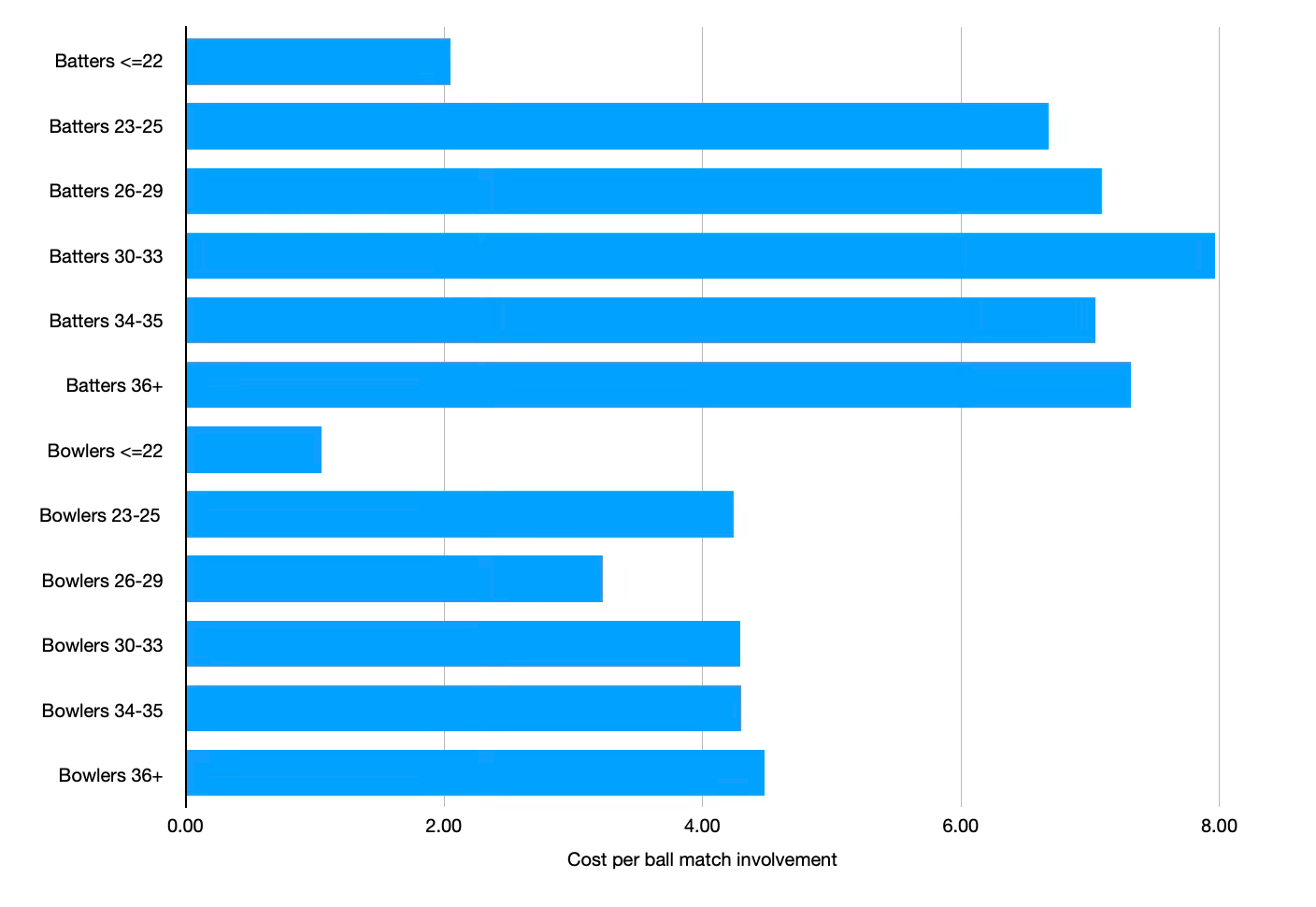

The chart here shows the inefficiency clearly.

We can see that except for young batters (aged 22 or below), batters always cost a greater amount of lakh per ball involvement than bowlers. Often, not far off double the amount.

While there might be some argument that batters have the potential to face more than 24 balls (the maximum number of balls per match which bowlers can bowl), only 16/37 (43%) of the most prominent batters in this season’s tournament (150+ balls faced) were able to have a balls per dismissal figure above 24. Mostly by not very much. The scope for this to skew these figures is quite low.

So, how can this dynamic make sense? Therefore, in simple terms, batters are overvalued in the marketplace based on their on-pitch performance. We know that bowling-strong teams have a greater chance of success than batting-strong teams, yet the data above illustrates that this is not taken account by the teams at auction.

Essentially, there is a gigantic market inefficiency where batters are grossly overpriced. I don’t think that this is the entire explanation, but part of the reason could be due to the high reputation and brand power of the Kohli’s/Rohit’s/Warner’s/Dhoni’s of this world, despite their performances and match involvement not necessarily always being in line with such price points. Would Bumrah and Rashid Khan have similar marketing value - I’m not sure, but I doubt it.

This is where IPL teams have to make the clear decision between being a marketing enterprise making money for their owners, or becoming a serious sporting organization. There are signs that Rajasthan Royals are already well on the path to becoming the latter, but most other teams aren’t really on that same path.

One other thing you may have noticed from the chart is that players aged 30+ average a higher lakh per ball involvement cost compared to players aged under 30. Does Dan Christian’s famous quote ‘Old guys win stuff’ hold true? In short, no it doesn’t. At least, not currently. The oldest team in the IPL this year was RCB, who are highly likely not to qualify. They had a weighted appearance average age of 30.52.

Further, as you’ll see here, when splitting up both batting and bowling performances into age brackets, there’s no evidence that veteran players perform any better than any other age in this year’s IPL. In fact, they perform worse than most other age brackets, particularly for one metric - non-boundary strike rate. More on that later.

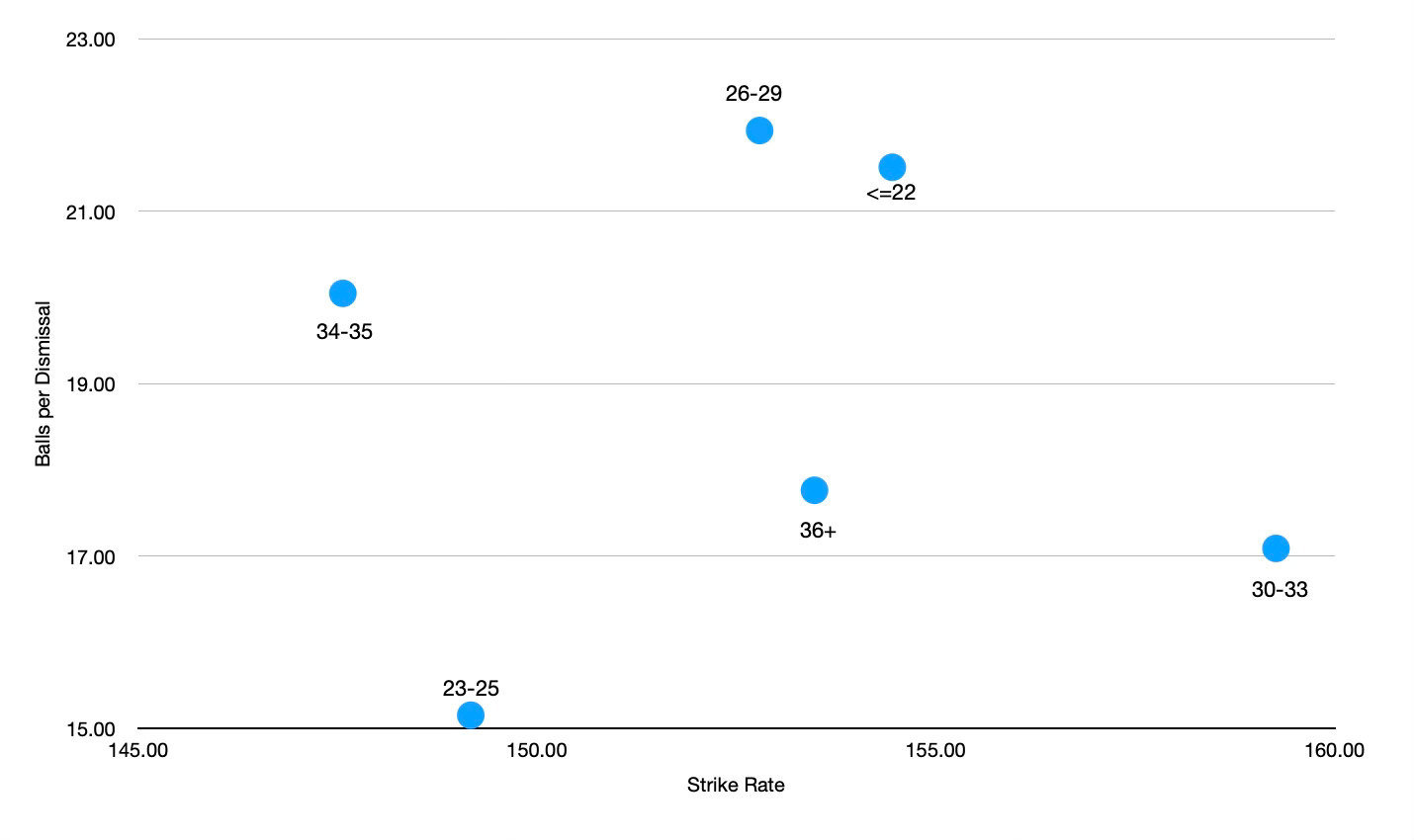

Here we look at the combined performance of all IPL batters in this graphic below, showing strike rate (intent) vs balls per dismissal (stability) split by age bracket:-

As you can see, 34-35 year old batters struggled with their strike rate - the lowest of the six age group brackets - while 36+ year olds were fairly midrange with their strike rate and low for balls per dismissal. There is literally no evidence here to suggest a logical on-pitch performance based reason as to why older batters cost so much compared to younger ones. Again, illustrating a clear market inefficiency with 36+ year old batters costing 7.32 lakh per ball faced.

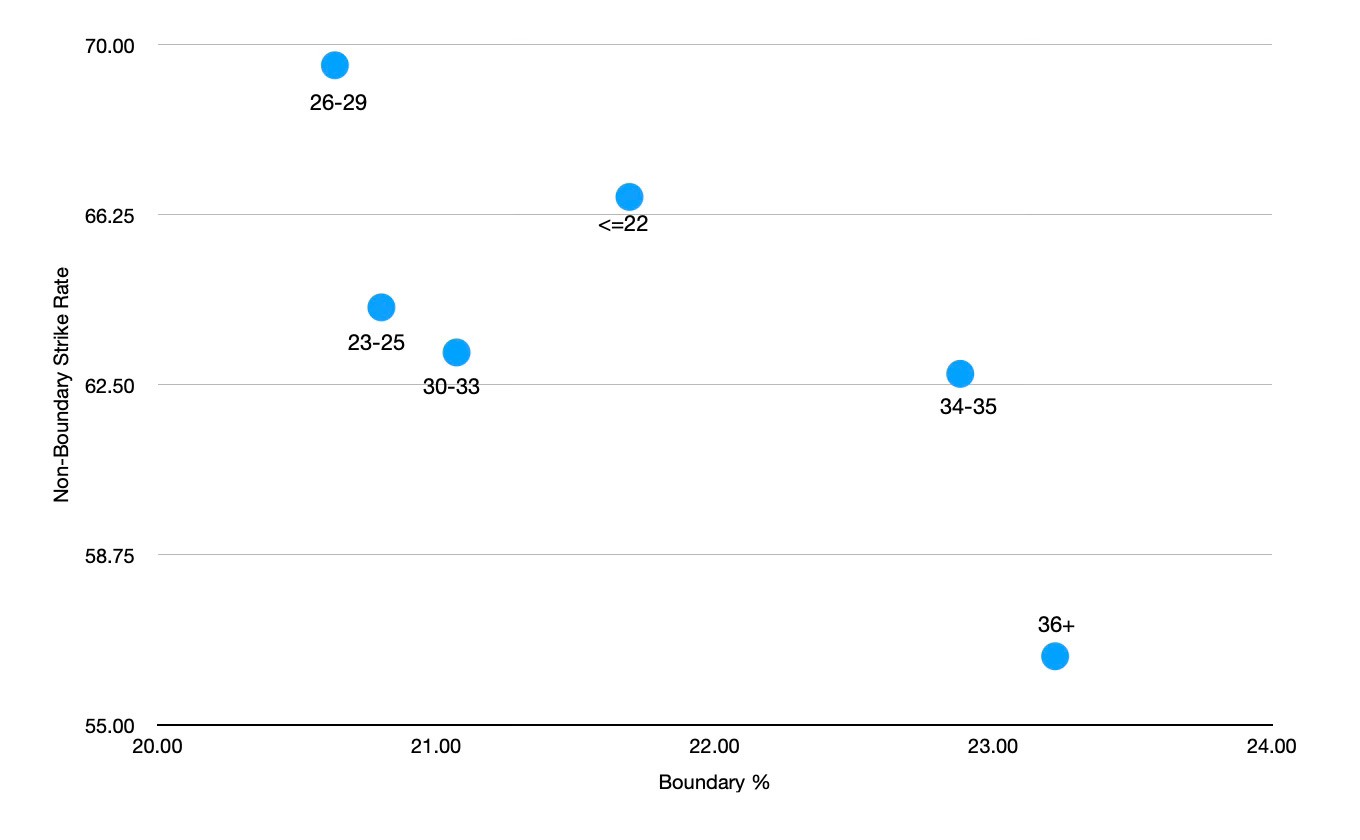

A look at run production from batters gives some further insight:-

Look at this - as batters get older, they score a higher percentage of boundaries, but their non-boundary run production drops off markedly. This was also true in previous seasons, and is clearly not a one-off this season.

Here we start to consider the age development of players at mega auction. If you are looking to buy a batter who is 32-33 years of age, you want to be pretty sure that they are either 1) an outstanding boundary hitter who can make up for a drop-off in non-boundary run scoring or 2) one of the fittest players in the tournament who has such a high peak to decline from.

Of all the main batters in the IPL aged 36+, only Dinesh Karthik was able to produce a non-boundary strike rate of 70+ (and only just). David Warner, Rohit Sharma and Wriddhiman Saha all have non-boundary strike rates below 50 in this year’s IPL, while MS Dhoni, Shikhar Dhawan, Andre Russell and Mohammad Nabi aren’t particularly highly ranked via this metric either.

Making the highest expectation decision on when to move on from high-reputation veteran players is one of the toughest decisions for a franchise to make. But make no mistake, failure to do so can leave a team struggling for an entire auction cycle. Re-iterating - when you are buying a 32-33 year old at mega auction, you aren’t just buying a player for their value now, you’re buying a player likely to decline in certain ways throughout the next auction cycle.

In the first part of this series, I wrote that “a young player, for example, should be more valuable to teams in a mega auction, and an older player more valuable to teams one year before a mega auction.” This assertion is backed up here by the above analysis - if you buy an older player one year before a mega auction it is simply a short-term, one year proposition. You don’t have to worry about their decline as they get older. However, you do have to worry about their decline if you pick up the player at a mega auction, with a planned three-year retention window and limited replacement prospects in an inflated-price mini auction environment.

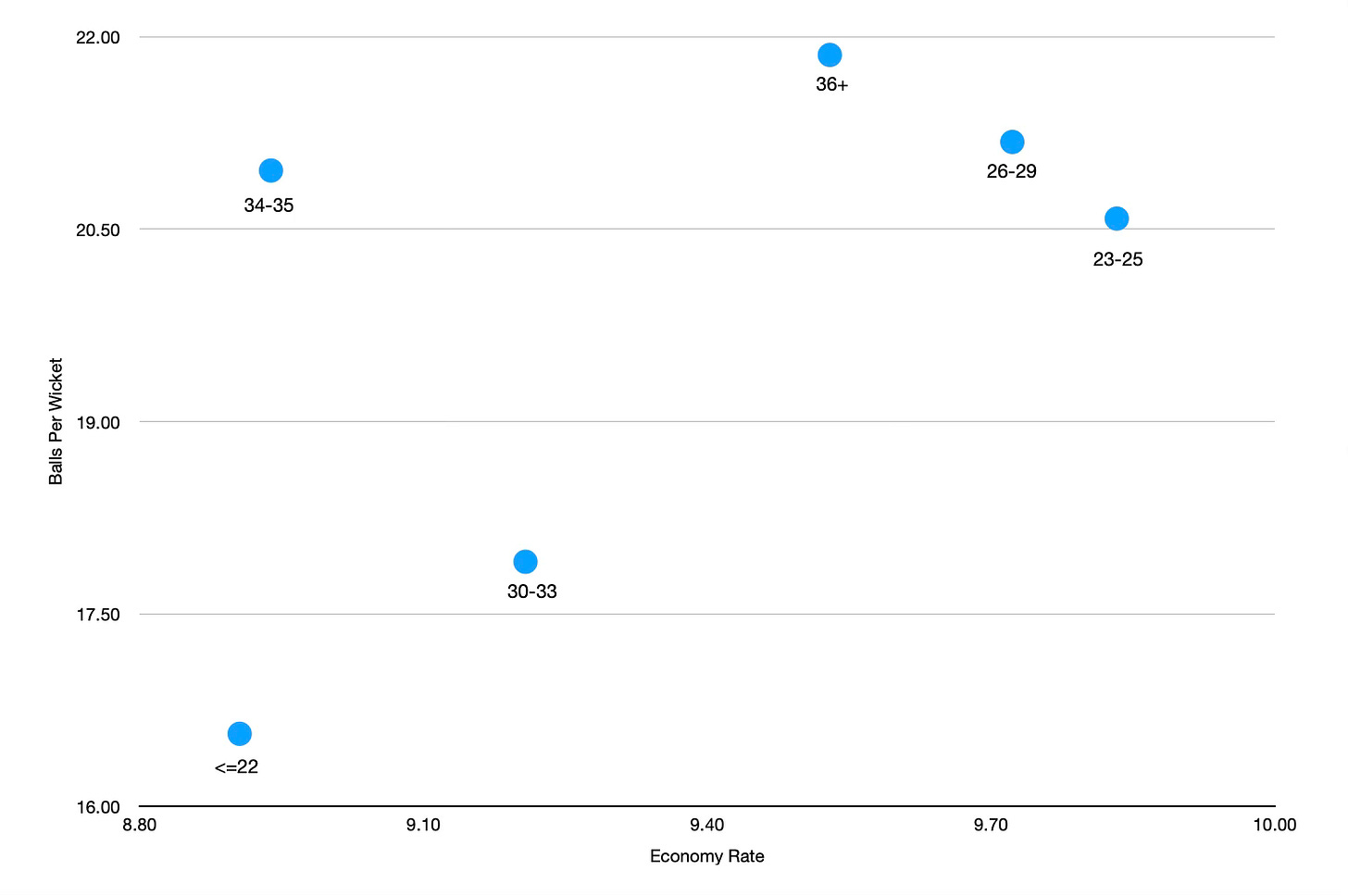

Bowlers data suggested a similar conclusion where there was no perceptible on-pitch performance advantage shown from veteran players.

34-35 year olds had a relatively low economy rate but struggled to take wickets on a regular basis, while 36+ year olds were far worse, with the worst balls per wicket average across all age brackets and costing 9.53 runs per over in the process.

Again, young players impressed with the lowest economy rate and balls per wicket figures, although the chart also shows there’s scope to suggest that this is a ‘breakthrough effect’ and as they get older, they get worked out to some degree. Either that, or the likes of Noor Ahmad, Matheesha Pathirana, Mayank Yadav and Harshit Rana are potential generational talents.

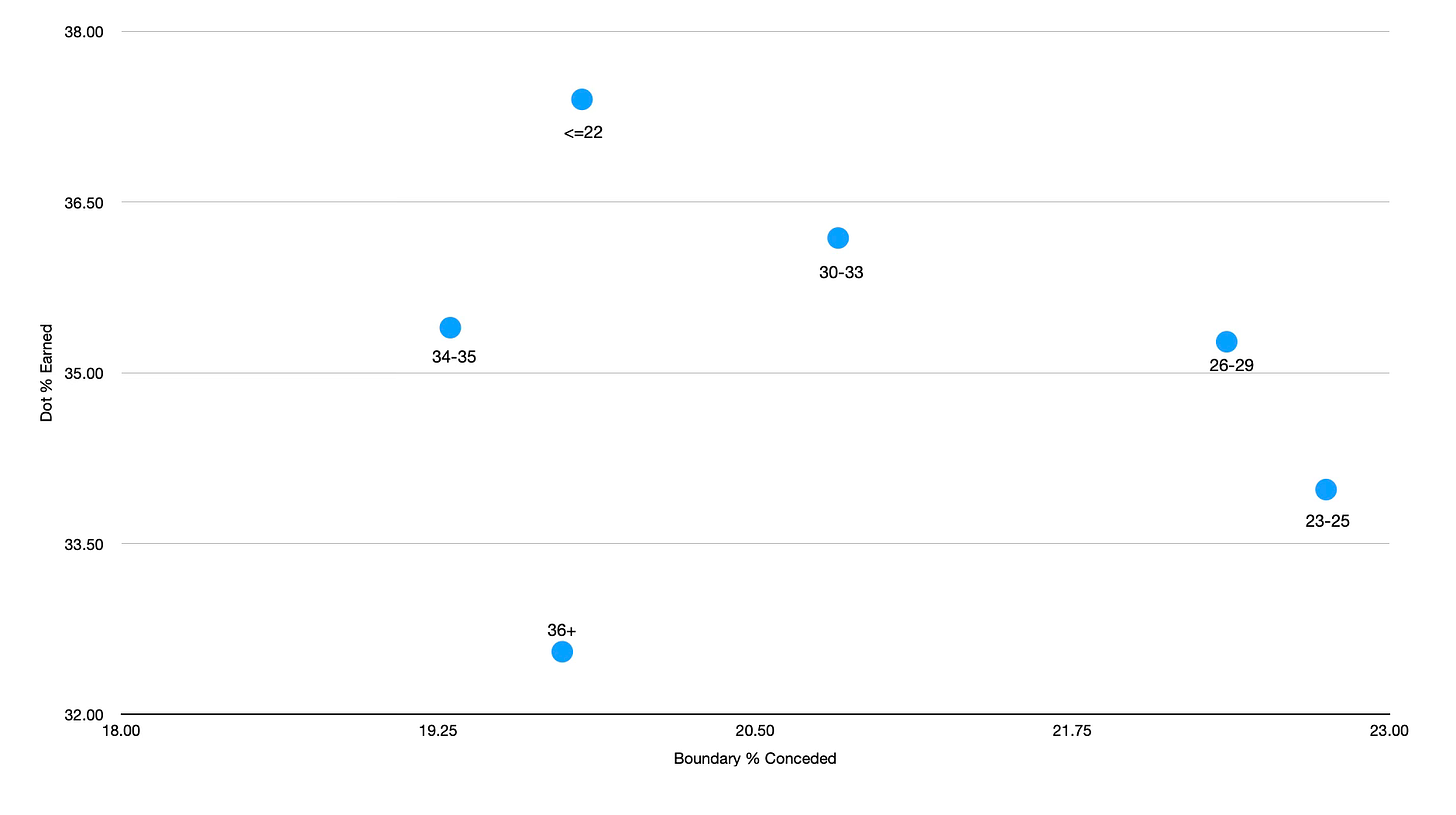

A look at run prevention metrics also is useful:-

While veteran players were able to stem the flow of boundaries more effectively than younger players, they were often less able to earn dot balls as frequently, particularly those bowlers aged 36+. Although boundary prevention is certainly a very positive attribute for a bowler, this doesn’t give enough support to suggest any argument that the wildly differing costs for older bowlers compared to younger ones is efficient.

Remember, bowlers aged under 22 who have played in this year’s IPL cost just 1.05 lakh per ball bowled, while 36+ year olds cost 4.48 lakh per ball, and 34-35 year olds and 30-33 year olds equated to around the 4.30 lakh per ball bowled mark. It would appear that teams have made a series of mediocre retention decisions, holding on to veteran players on big salaries far more often than they should.

With all this considered, how can smart teams look to take advantage of the market inefficiency? I don’t want to give all my thought processes away, but what I will say is that there is a vast difference between the on-pitch output of veteran players and the cost attached to recruiting them. That’s not to say that older players can’t ever be good value for money, but teams would be well advised to avoid paying big money for them early in an auction cycle, and also to avoid retaining them on big contracts when evidence suggests the decline is starting.

Just as in other forms of investment, ensuring that you don’t overpay for a commodity is vital. All players are just that - a commodity which has a fluctuating market value. Falling into the trap of paying over the market value for a veteran player who is likely to decline is something which a lot of IPL teams have done, and continue to do so.

Anyone interested in discussing how I can help their team with strategic management and data-driven analysis, or contribute to any media work, can get in touch at sportsanalyticsadvantage@gmail.com.

One more contributing factor to the low non-boundary strike rate for older players, would be the non-willingness to rotate strike especially while chasing. So many times DK and Russell have refused to take that single (atleast going by the eye test).

I am sure there is much more to this but this shouldn’t be ignored or somehow factored in

Very interesting column, the cost-per-ball-by-age-bracket numbers are quite stark when you see them presented this way!

Re: this batting vs. bowling inefficiency, my intuition would be that there are a couple other factors that give batters more relative value: 1) bowlers' season-over-season performance is more variable than batters, and 2) even if you can get a core of bowlers who you're confident in, they are more prone to injury and/or load management. MI in 2022 would be a good example of a team theoretically heeding your advice, then getting burned with only 2 out of a possible 6 seasons played in the cycle for bumrah and archer. Same with GT - they were carried by Shami and Mohit last year, this year no Shami and Mohit is going for 39.4 at 11.25, yikes!

Beyond IPL, I'd point to Lahore in PSL as suffering from the curse of unpredictable bowling performance...