With the IPL starting today (Sunday, 19th September 2021), I thought I’d put up a quick post to show the dynamics of various regular batters in the tournament across the last couple of years.

As the 2020 IPL took place in the UAE, and the restarted 2021 competition also is (having played the first half in India), I want to look at player data from 2020 onwards, which should give us some nice insights into potential player levels for the remainder of this tournament. This is going to be pretty basic player data - none of the fancy stuff I use for detailed player recruitment which I can’t really share on here - but I think it should be pretty interesting reading, and will have the potential to challenge a lot of people’s pre-existing opinions. For this, I’m looking at those who have batted/bowled 200+ balls.

We know that around 85% of teams win the match when they win the boundary percentage count, I’ve written about it enough times already. In addition, the vast majority of teams with a +1% net boundary percentage over the season qualify, so these are pretty strong drivers of success. In short, hit more boundaries than your opposition on a regular basis and you’ll do pretty well.

Life’s a bit more complicated than this, which is why I have a boundary production model for both batters and bowlers (which sadly has to be reserved for teams who I work with), and of course we must look at boundary prevention from bowlers too, but what I’m trying to say here is that scoring more boundaries than your opposition is key to success. It can be via ultra-attacking batting, like we did at Birmingham Phoenix this summer in The Hundred, or it can be down to having world-class bowlers, which Southern Brave did this year and the likes of Sunrisers Hyderabad or Perth Scorchers managed a few years ago when at their peaks.

But the reason why I talk about this is pretty simple. Because actually the batters you pick should be dictated to by your bowling group. It’s why I don’t think Dawid Malan is a good fit for England or Punjab Kings, but at more ‘bowling strong’ teams, he’d be a useful addition. We have to consider the expected team dynamics with recruitment, not just whether a player is simply good or bad. A good player in a team which doesn’t suit him can look bad, while a bad player in a team which does suit him has the potential to look better than they actually are. If you have a poor bowling group, you can’t afford to recruit any anchors. If you have an average bowling group, you can probably afford to recruit one, but what I call a ‘facilitator’ would be a better choice - a batter whose presence in the team facilitates everyone else to play to the maximum of their ability. If you have a great bowling group, like Sunrisers or Perth did back in the day, you can probably get away with two anchors.

Anyway, on to batting data. Here’s how IPL batters work out from 2020 onwards when comparing stability (balls per dismissal) to hitting (boundary percentage). This dynamic usually has a reverse trade-off whereby hitters don’t last that long while stable players (anchors) don’t hit very well. Anyone who can do both is elite (for example AB De Villiers over many years), while anyone who can do neither - well, it doesn’t reflect positively on their ability when judged over a decent sample of data.

Some of the players featuring towards that ideal top-right corner offering stability and hitting include Pollard, Jadeja and the previously mentioned De Villiers - these players are a great blend of the two attributes. What is also interesting is to see the sheer volume of players here who have above 20 balls per dismissal, which is a pretty rare dynamic compared to other leagues.

IPL teams often have this dynamic of wicket preservation and then ridiculous attack at the death and this is to an extent illustrated here, with a lot of batters having mid-high 20s for balls per dismissal and then mediocre 13-16% boundary hitting percentages. This does look to be a preferred strategy from IPL teams and I’d contend whether it is optimal - I think better strategy would be to bat a bit deeper with genuine frontline bowlers who can hit, and then have less emphasis on wicket preservation. A relatively efficient recruitment market should be giving these low boundary-percentage players a pretty low market value, particularly those from the overseas player pool.

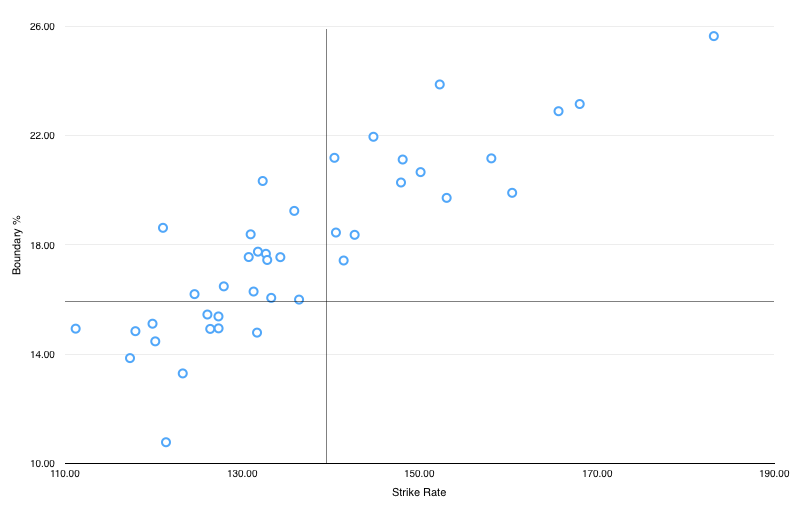

Here’s a little bit of information which is logical, but you might not have thought of. I have written about it before, but you might not have seen it. Essentially, a batter’s strike rate has a direct relationship with their boundary percentage. Unless you’re an absolutely elite non-boundary scorer (e.g. very good at running singles, and turning ones into twos) then it’s basically impossible to strike at 140+ when you hit below 16% boundaries.

You don’t believe me? You think dot ball avoidance is great? You think boundary-hitting is over-rated? No player names needed, but each point in the chart below represents the same 200+ balls faced batters. Let’s see how this played out in the IPL from 2020 onwards:-

Look at this. Not a single player hitting above 140 in this time frame - and there are 15 of them to the right of the vertical line - hit at below 16% boundaries. In fact, no-one hit below 17% boundaries either. In short, it’s basically impossible to find a player who can strike over 140 when they’re a below-average boundary hitter. So, if you’re an IPL fan, or just a cricket fan, you want to be asking why your team is recruiting players - particularly for decent money - who hit below 16% boundaries when you know that 1) boundary-hitting has a huge relationship with overall strike rate and 2) that around 85% of teams win when they hit a higher boundary percentage than their opposition. How many teams know this? I don’t think many - the ones I’ve presented this stuff to have been pretty amazed by this sort of stuff, and it’s very, very basic, first-level strategy.

Some players try and make up for their lack of boundaries by being strong at running between the wicket, and there’s a clear difference between two types of batters here. Firstly, there are players who have low boundary-hitting numbers because they lack power and an attacking mindset, and secondly there’s a different type of player who have low boundary-hitting numbers because they are too risk-averse and try and ‘take the innings deep’ before attacking. You can tell who these players are easily - they have a REALLY high death strike rate despite having mediocre strike rates in other phases. The first type of players simply shouldn’t be recruited, while the second type of player needs to be pushed into attacking earlier or only be recruited by a strong bowling team, and probably not for a lot of money.

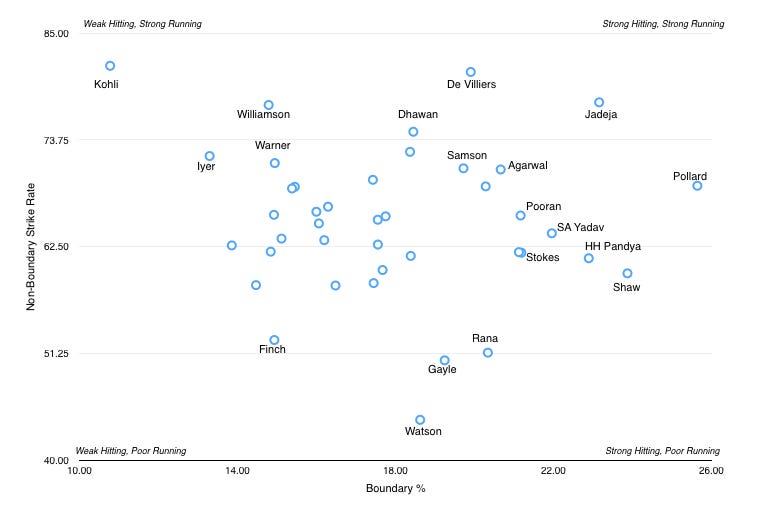

Non-boundary strike rate is a really good metric to use to work out how productive a player is when they don’t hit boundaries. It has a broad correlation with dot-ball percentage but also takes into account a player’s ability to run twos as well, so in my view it’s a bit more useful than simple dot-ball percentages.

Some players - the ones who evidently maximise their scoring options - are good at boundary-hitting and non-boundary strike rate - but they are pretty rare. Again, usually players are good at one thing or another (because if you swing at a lot, then you’ll end up with dot balls too because you don’t connect with everything). Other players take the approach of trying to connect with as much as possible but without the boundary intent, and we can see who the players are in each bracket here:-

The trio I mentioned before who impressed - De Villiers, Jadeja and Pollard - impress again here as batters who combine good hitting with good running, while the likes of Kohli and Iyer are firmly in the ‘rotators’ dynamic, where they don’t hit a high percentage of boundaries but will try and score off as many deliveries as possible. The problem with that, as we’ve seen already, is that you can’t strike at 140+ by doing that! Certainly it would be extremely questionable selection strategy from India to pick Kohli and Iyer in the same team in the upcoming World Cup - it would place huge reliance on their other batters to hit boundaries.

It’s also interesting to see David Warner here as a low boundary-hitter. This is the current version of David Warner - responsible, dot-ball avoiding Warner, as opposed to the player who struck fear into opposition bowlers for years. Between 2015 and 2017, Warner struck at over 21% boundaries in domestic T20 cricket so this is quite the change in approach for him - I’m not sure that change is for the better, and if Sunrisers Hyderabad are to have any chance of a miraculous turnaround in this season’s IPL, then they will need that previous version of Warner to come to the party.

Enjoy the match tonight, and don’t forget to subscribe for free and to comment if you have anything you’d like to discuss. I’m also going to be featuring on The Cricket Podcast tonight with a live post-match stream to discuss today’s match, Chennai Super Kings versus Mumbai Indians, and you will be able to find that here shortly after the match finishes.